Our Blog

Looking Back

February 1951

Milford’s Own Trailblazing Superstore

Photographs courtesy of Sadie King

Historical material provided by Diana Kuhnell

Today, we’re sharing a fascinating story from Milford’s past. Have you ever heard about the Farm and Home Center?

Did You Know?

Did you know that the Farm and Home Center in Milford, Ohio, used to bring in over $2,000,000 a year, even though it was in the middle of nowhere? Don Florea, a local farmer, made this possible by turning an old chicken house into a one-stop shop for everything you could think of. It was so big that it even had the largest frozen-food locker in the Midwest, with 2,500 compartments! Imagine a place where you could buy anything you needed – from a refrigerator to a haircut – all under one roof.

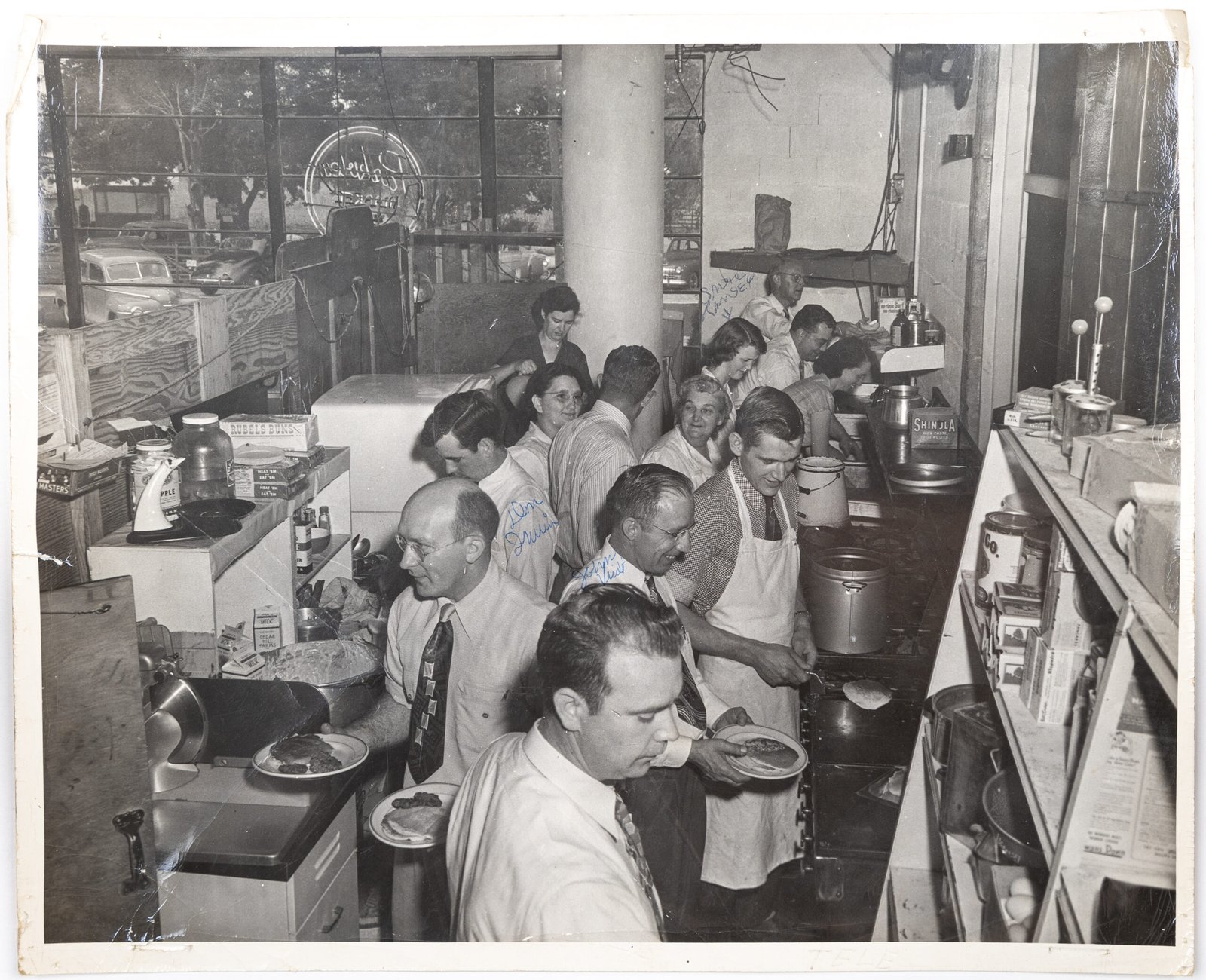

His store was featured in the national article below. Photos courtesy of Sadie King, who once worked at the store.

(This story appeared in This Week Magazine on Feb 18, 1951)

Superstore in a Cornfield

by Dick Ashbaugh

Photographs by Joe Monroe

Here under one roof you can get the valve ground in your car, buy a refrigerator, a house, or even get your hair cut. It’s a colossus in a cornfield – meet Don Florea, the man who dreamed it up.

Milford, Ohio

Smack in the middle of nowhere, miles from any superhighway or population center, bordered only by a minor state route, stands a country store that grosses over $2,000,000 a year.

Strangers stop along the roadside and say, “We’re looking for the Farm and Home Center. Where is it?” A farmer grins, “It isn’t any place exactly.” And it isn’t.

A mile from the tiny village of Milford, Ohio, the rolling cornfields break abruptly against a plateau of parking areas, driveways and lawns. Approximately in the center stands the main structure, a mammoth, spanking white, one-story building rising out of a sea of shoppers’ cars.

This is the Farm and Home Center, a colossus in a cornfield, which operates on the starkly simple principle of having everything under one roof. It sells more automobiles, television sets, tractors, baked goods, wire fencing, baby chicks, beefsteaks and barn paint than any other single dealer in an area that includes Cincinnati, Ohio’s second largest city.

It will sell a hunter his gun, shells, clothing, camping equipment, and grind the valves in his car. It will pack him a box lunch for the afternoon or a year’s supply of canned food – and a barber will cut his hair. The Center will cash his check, provide him with a hunting license, and cover him with insurance. If his trip is successful, the Center’s packers will process the game and stow it in the largest frozen-food locker in the Middle West – an icy cavern tiered with 2,500 six-cubic-foot compartments.

He’s an Oddity

Proprietor of this fabulous experiment in rural merchandising is an amiable, soft-spoken 43-year-old dirt farmer named Donald R. Florea, who built the business from an abandoned chicken house.

In a highly competitive, small-margin business, Donald Florea is an oddity. If he ever becomes a millionaire, which seems highly probable, he will be a reluctant and embarrassed one. His chief characteristic, backed by overwhelming evidence from employees, dealers and customers, is a mixture of complete honesty and straightforward but kindly shrewdness.

The Center’s policy of operation is so simple it startles worldly businessmen. Its merchandising tricks are original and advertising through the usual mediums is almost microscopic. However, the entire establishment jumps with dozens of amusing and imaginative services for the 5,000 customers who cram the store on a busy day.

There is a casual, rambling air about the place. On Saturdays entire families lose themselves among the 28 departments and seemingly endless aisles of the one-acre building. They chat, gossip, eat, buy, trade and dicker amiably with the Center’s 110 employees. Florea himself wanders happily among them, stopped a hundred times an hour by a crop farmer, chicken breeder or dairy man wanting the latest tips on feed or equipment.

Free Television

Glancing through the plate-glass windows he chuckles as he watches a stable of 20 Shetland ponies entertain the customers’ kids. Under a huge circus tent to the rear, several hundred more small fry shout warnings at their cowboy hero, as he two-guns his way across the Center’s movie screen. Later the older folk will take over the tent with square dancing, cider and, the modern touch, a battery of television sets in a darkened alcove – all free of charge. Keeping a watchful but kindly eye on the throng is Florea’s own police force, a corps of trained employees who scoop up lost children, direct traffic and guard the parked cars.

Pausing a moment at one of the check-out counters, Florea is approached by the chairman of a church bake sale. She would like space for the following Saturday. “Certainly,” he replies. “We’ll put you in the entrance lobby. Best spot in the store.”

The chairman is properly grateful and then adds apologetically, “I’m afraid your baked-goods department will suffer. Naturally we’ll undersell you.”

“Go to it,” he says. “I hope we lose our shirts.” He knows this is a remote possibility. His customers will clean out the sale in an hour. All the cakes and bread the women could bake in a month would scarcely dent the Center’s turnover which, in bread alone, runs as high as 3,500 loaves a day.

Added to this, Florea knows that, in due time, the church members will buy a brooder house, a new refrigerator, a 100-piece china set, an album of Crosby records, a side of beef or a dozen pairs of nylon hose. It is even possible one of them may want to buy an 85-acre farm with a modern seven-room house. If so the Center’s real-estate division will gladly oblige.

Still hovering at the check-out counters, the nerve center of the store, Florea makes a casual inspection of the cash registers. The battery of big electric jobs must be emptied at least once an hour on a busy day. If there is a scarcity of change, he nods, and a messenger starts for the rear offices for a fresh supply from the one ton of wrapped coins trucked in that morning from the Milford bank.

Despite the nimble-fingered cashiers, Florea’s special pride, the customer lines grow longer. Another nod and white-aproned errand boys swing down the lines with open boxes of lollipops for the squirming youngsters and nosegays for the ladies-in-waiting. Before the day is over these little good-will stunts will help bring $26,000 into the cash drawers.

$45 Beginning

Twenty-five years ago, a stocky farm youth who hated everything in school but vocational agriculture approached a neighbor near his Blanchester, Ohio, home. “I’d like to buy that Poland China sow,” he said.

“Want to dicker?” asked the farmer with a grin.

“No, just buy. How much?”

“Well, Donald, I’ll let you have her for forty-five dollars.”

“Sold,” said Donald Florea, and then gulped as he counted out the $45 he had taken almost 10 years to save. The sow was family-minded. From two litters, young Donald saved 15 pigs. Moving fast, he traded the pigs for chickens. Bringing them along carefully, he eventually owned over a thousand pullets, plus three registered Jersey heifers. The original $45 had grown into a substantial chunk of capital and young Florea was a confirmed farmer for life.

Squeaking through school, he went to work for Henry Feldman’s chain of feed and grain stores. In a short time he was manager of the Blanchester and Norwood stores. But this was practically city life and Donald Florea wanted no part of it. Carefully he looked over the extensive Feldman properties. Out on Route 28, near Milford, was a sadly depleted 48-acre farm with a run-down chicken brooder.

It’s a Jinx

“Don’t be foolish, Donald,” said his boss. “That place is a jinx. I lost fourteen thousand dollars out there last year.”

“One year,” pleaded Donald. “Then, if I can’t make it, I’ll come back to the store.”

A year later young Donald was back in the store – with the debt wiped out and a $3,000 profit. He also had a plan to buy the place. Mr. Feldman laughed, “Well, I lose a good manager, but you’ve earned your chance.”

Ownership was only the first step. This was a great egg and poultry center but, to young Florea, the producers were doing too many things wrong. Quietly, but insistently, he pointed out the errors. He kept harping on proper feed. “It’s the all-important thing,” he said. “Everything a chicken eats goes into the egg.”

Accustomed to accepting egg production as an automatic act of nature, controlled only by the hen, his listeners scoffed.

Florea answered by introducing a harmless chemical into the mash. One set of chickens produced eggs with bright green yolks, another group, ruby red. He raised chickens in five-gallon glass jars, training one group on his special blend of commercial feeds. They grew nearly twice as fast. The farmers were convinced.

From this start grew the idea of a controlled cycle. Florea would finance the expansion of a promising young producer. Then, working night and day, he would personally supervise the flocks. When they reached market weight he would buy them back at top market price, process the poultry, and sell it to a steadily growing list of commercial customers. The producer in turn, would purchase more baby chicks, more feed and equipment, and start over. Everybody made money.

Today the idea has been expanded to include all forms of livestock.

Recently a farmer walked out of Florea’s office folding a $6,000 check for a herd of prime-beef cattle. He started through the store and then paused thoughtfully before a line of shiny tractors. Across the aisle was a group of television sets, and his wife wouldn’t exactly run him out of the house if he bought a new home freezer. Before he reached the door, $2,800 of the check had gone back into the Florea cash drawers.

Although he was by now a farmer-merchant, Florea still worked in overalls, farmed his own land and counted his chickens both before and after they were hatched. He had married and started a considerable family. The Floreas had eight and eventually would have 11.

A New Start

One January night in 1946 Donald Florea noted with satisfaction that his books would show a $300,000 gross for the previous year. He started out for a final inspection of the buildings, stopped and then broke into a frantic run. A flickering light was coming out of the brooder houses. The employees on duty swung into action, but long before the volunteer fire department roared out Route 28 the fire was out of control.

In one night-long holocaust, the work of years was wiped out. At dawn Florea sat on an upturned water bucket and looked at his smoke-blackened employees. “Well,” he said calmly, “shall we start over again? There’s some insurance and I’ve got a little money in the bank. But, most of all, I’ll need the moral support you fellows can give me.”

Unhesitatingly it came. They wanted to work for him. Almost before the ruins cooled he had contacted a firm of architects and engineers. Several days later, chaperoned by the local Milford banker, Florea walked into a leading Cincinnati bank, asked for a loan of $150,000. “I received,” he says in retrospect, “probably the quickest rejection in the annals of banking.” Under no conditions would the bank consider a rural loan of that size.

Undismayed, Florea began talking quietly. He told what he had done in a few years. He outlined his prospects and future plans. At the mention of his annual gross, the banker’s concrete exterior cracked slightly. He promised to send out a team of investigators.

The investigators ran into some surprising evidence. Wherever they went, residents of the area spoke highly of Donald Florea. They pointed out that the frozen-food locker he had operated was absolutely necessary. They insisted the district would suffer if the firm weren’t back in business forthwith. Completely convinced, the bank granted the loan.

The results came as a surprise. Everyone had pictured a re-building of the original structure. When the surveyors finished staking out the foundation lines of the new plant, there were whistles of amazement. “Bigger than a football field,” was the general comment.

Fourteen months later, with a construction cost that had rocketed to $450,000, the Center opened with a week-long carnival.

At first merchants in nearby small towns were resentful of this giant on their doorstep. Florea called together the businessmen’s clubs, seated them before platters of the Center’s fried chicken, and out-lined his convictions. Thousands of new customers swarming through the area would certainly mean business for all. In a few months he was proved correct.

“Too Many Compliments”

It would be difficult to find any resentment among residents of the surrounding townships – particularly the kids. They remember rides through the snow in the Center’s big horse-drawn sleigh, the thousands of toys provided at less than cost and the sacks of candy and the dozens of baskets of apples scattered around the store with the signs, “Help Yourself.”

Nobody would deny that this is good business – least of all Donald Florea himself. At his desk, in the rear office, he frowns as he examines the latest batch of notes from the suggestion box in the lobby.

“I wish people would be more critical,” he says. “There are too many compliments here. If they would only hop on us oftener we could do a better job.”

His customers wouldn’t be surprised at that statement. They know he means it.

The End

Photos below courtesy of Sadie King, Farm and Home Center circa 1950

(special thanks to Mark Birkle for digitizing)

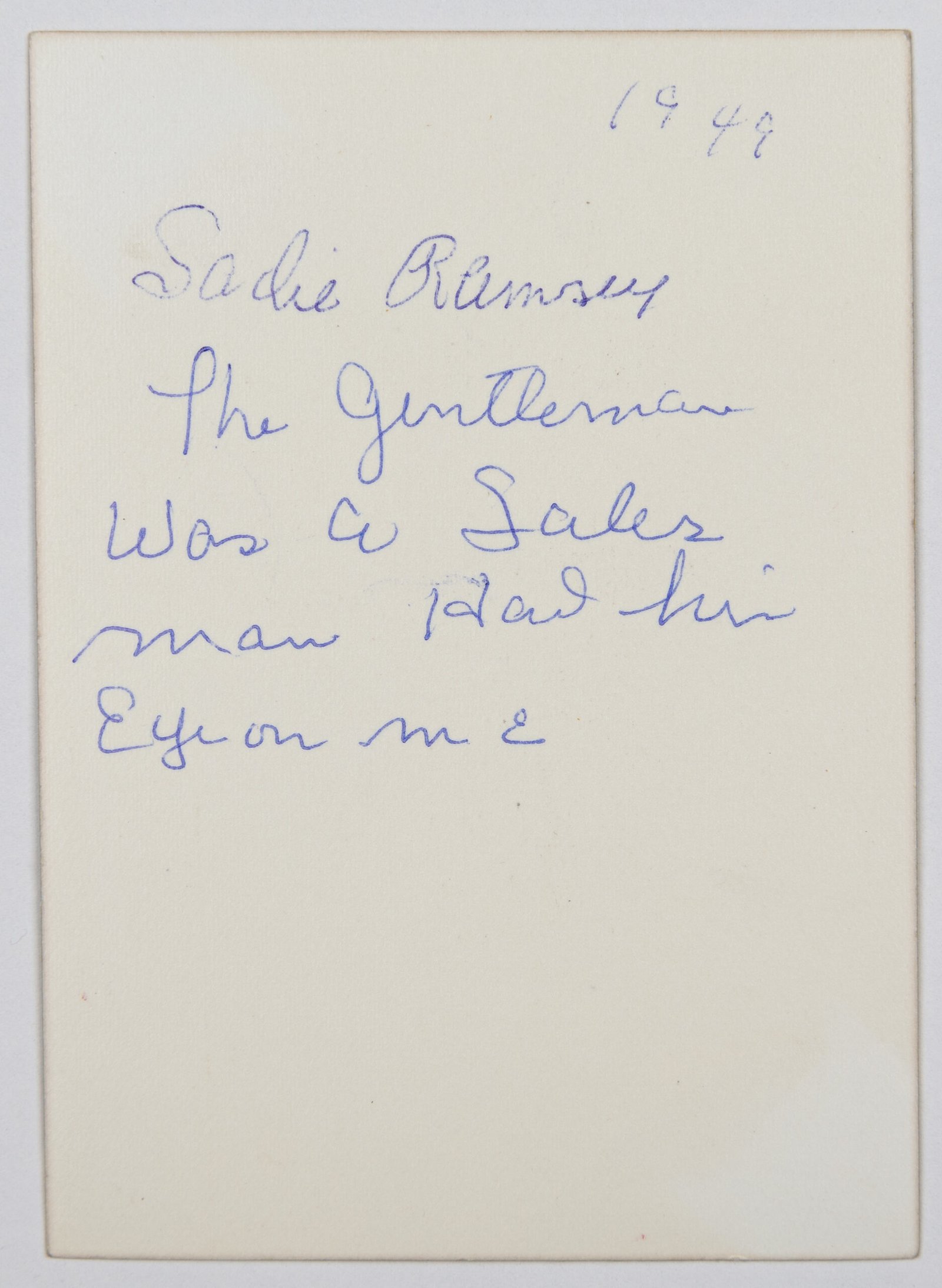

Photos below of Sadie King and a Farm and Home Center salesman

Caption on the back…

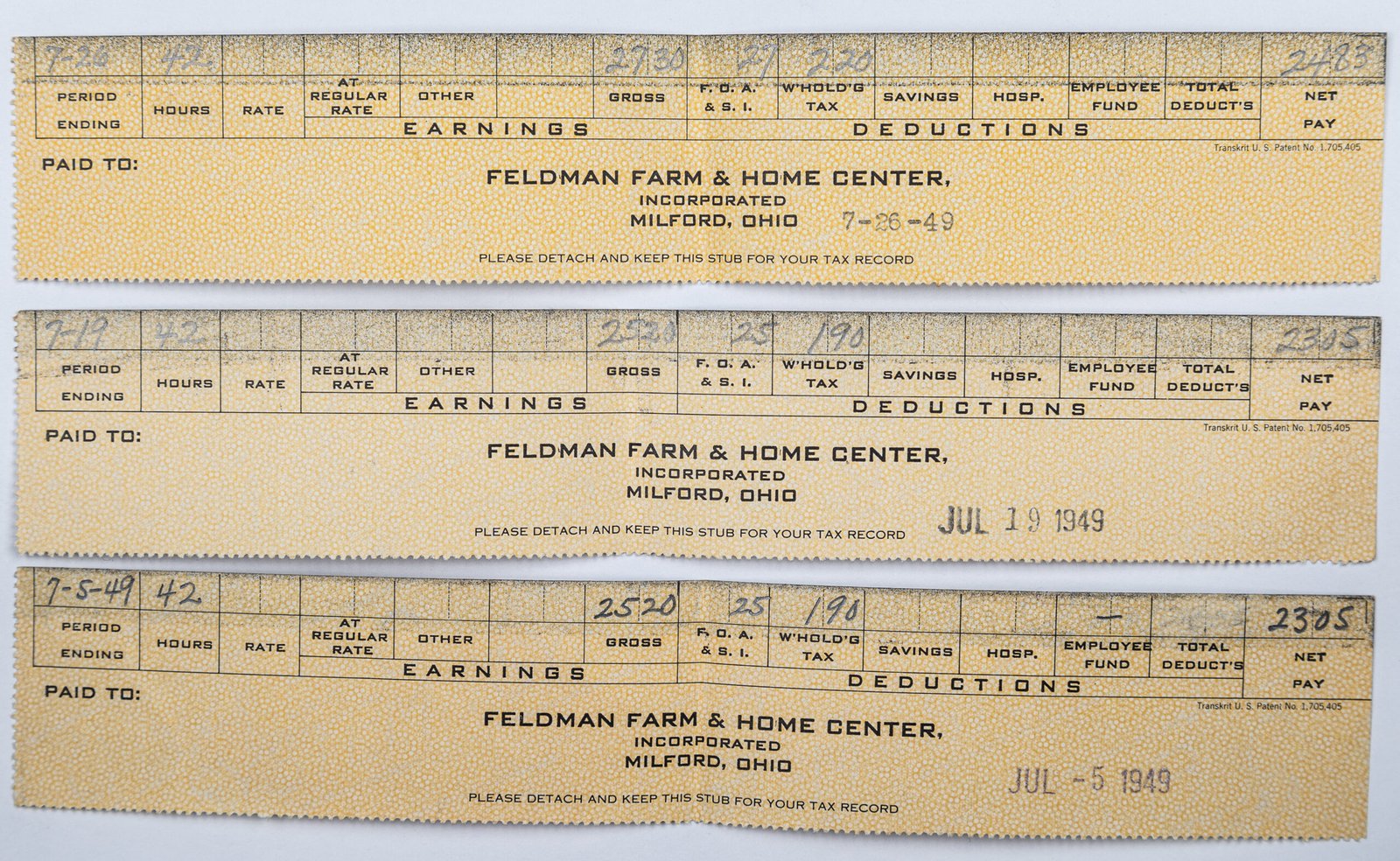

Pay stub with hourly rate of 67 cents

What happened to the center?

From the Milford history book Bridges to the Past

Farm and Home Center (page 187)

One dealership was called the Clermont Sales & Service, owned by Homer Coyle. It was located on Farm and Home Center property (Rt 28). On December 5, 1950, the Miami Valley News reported: “Homer Coyle is now located at 317 Main Street with a nice selection of clean and used cars—expert body and fender work, Henry Humphries.” He continued at that location until August 5, 1954.

(From page 338)

The Henry Feldman Feed and Poultry business was originally at 128 Main Street. It was moved to St Rt 28, one mile east of Milford, where Mr. Feldman had a poultry farm and hatchery. In 1944, Donald R. Florea, the second proprietor, added a frozen food locker plant, and it became known as the Feldman Poultry Farm and Food Locker Plant. A fire destroyed the facility on January 12, 1946, and Mr. Florea announced a new $250,000 building would be constructed to replace the locker plant. The Miami Valley News of February 12, 1947, announced the opening of the new Feldman Farm and Home Center, a 50,000-square-foot building housing a retail center with “One-Stop Shopping” that handled large appliances, hardware, clothing, dry goods, groceries, and meats, as well as a restaurant. A 1949 addition provided for more retail business.

Sale in 1950

In 1950, Mr. Florea sold the entire property to M. R. Theilman, who leased the original Center to Rink’s Bargain Barn. John P. and Edward Castleberry, former owners of Cedar Hills Farm, Inc. (founded in the 1920s), purchased the Center from Mr. Theilman.

Theilman retained his Mobile Home Residential Park next to the Center, which he had developed in 1961. Rink’s moved into the new Clermont Shopping Center on U.S. 50.

The Milford Advertiser of February 27, 1991, reported that the eight-and-a-half-acre property was sold to Murry Gutman, Hill Building and Construction Services on Montgomery Road, with plans to add structures to form a shopping strip mall, which has been completed.

Where would it be today?

Photos and info courtesy of Mark Birkle

749 OH-28 A, Milford, OH 45150

PROMONT HOUSE

Greater Milford Area History Readers meet at the Promont House.

906 Main St, Milford, Oh 45150